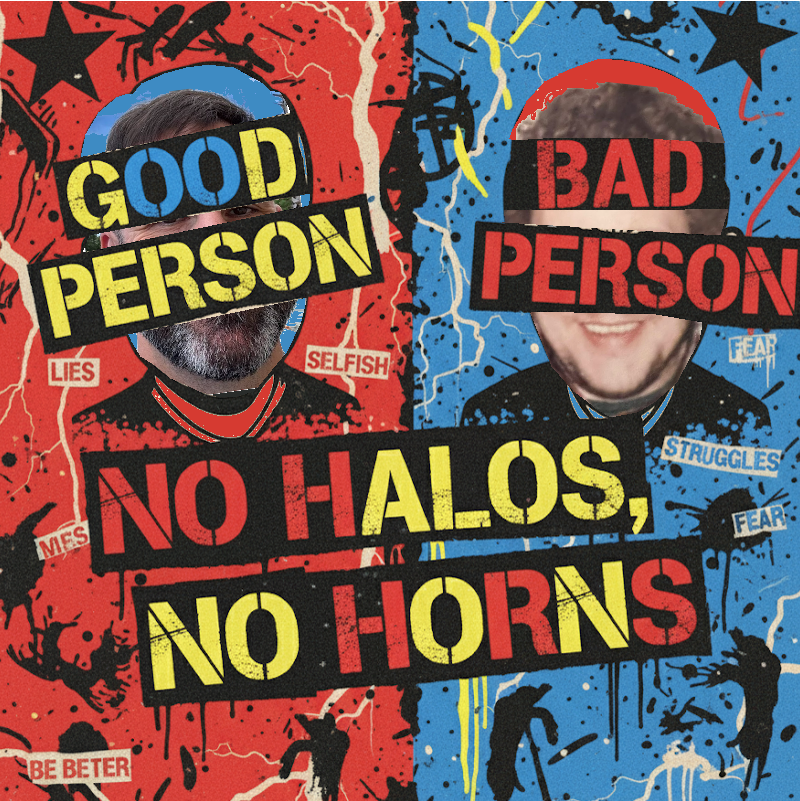

No Halos, No Horns

The Trap of Moral Labeling.

Donald Trump is not a bad person.

That statement ought to do some work, right? For some, it is a provocation.

“Of course Orange Julius Ceasar is a bad person! He lies about everything and demonizes people in dangerous ways! How could he not be a bad person?! What in MAGA is wrong with you?”

For others, it will be worth quoting something that confirms what they already know.

“Donald J Trump was anointed by God to save America. Like a modern King David he is not perfect but where it counts, he is the champion of the true America and will return us to our Glory!”

BAM! SEO baby.

But the point is, that statement has nothing to do with Donald Trump. Trump is not a bad person. He is just a person. So are you. So am I.

People are neither good nor bad. They are just people. It is what we do that carries the weight of morality.

The Trap of Moral Labeling

There is a trap in assigning a moral value to the whole of a person. Once we assign the label of “bad person” to someone, that will be the moral lens through which we view them. Same with a “good person”.

Let’s say Tom is at a corporate networking event. The only person he knows there is Jane, from sales. Jane seems to know everyone. But Jane never introduces Tom to anyone, even the senior VP down from their glass tower rubbing elbows with the peasants. Let’s look at this from two perspectives.

Tom thinks Jane is a bad person. Of course she didn’t introduce him to other people at the event; she was trying to undermine him while making herself look better. Jane is the snake that Tom always thinks she is.

Tom thinks Jane is a good person. She may not have introduced him to a few people she knew, but that is unfair to expect her to do without asking. After all, how does she know that she’s the only one there that Tom knows? She’ll see to helping introduce Tom, he just needs to be patient.

The truth is that Jane also does not know anyone else there. What Tom perceives as her knowing everyone is just Jane making use of the event for what it is; an opportunity to meet those she doesn’t already know.

Jane is just as nervous as Tom and overcoming that is taking all of her energy and focus. If she notices Tom keeping to himself, she might actively bring him into a conversation, but his needs are not the top of her mind with everything else she is trying to navigate at the event.

Want to dive deeper into practical ethics and moral decision-making? I explore these questions every week in Radical Kindness: Empathy as Rebellion—philosophy grounded in real life, not textbooks.

My Own Moral Trap

To further illustrate my point, I have lived in the moral labeling trap for most of my life. I grew up with a very abusive father. My earliest memories are shadowed by the fear I had of him. A fear that grew into anger as I moved through childhood into adolescence.

I don’t throw the label “abusive” at him lightly. He molested my twin sister. And me. He beat us for wrongs that only existed in his head. He gaslit us, he raged at us, he once very calmly and sincerely told me he was going to murder me.

At the age of six, I realized he was a Bad Person.

I also realized that I wanted to be a Good Person. Therefore I needed to just… not be him.

But he wasn’t a Bad Person. He was just a person. Did he do harmful things? Absolutely. Some three decades after his death I am still working through my trauma in therapy.

But despite the harm that he caused, he was not intrinsically bad. He had his own demons to overcome.

A childhood in the Ohio foster care system. A lifetime of poverty with no support from family or friends. He lived with fear, deprivation, and the sense that the world owed him more than he got. Not to mention severe mental illness exacerbated by decades of his own trauma and challenges.

This is not to excuse the harm he caused as a father. But once I labeled him the villain of my story, then that was how I would always see him. In his last days he spent a period from January to September 1996, where he found himself in jail, then in rehab, then in the hospital, all without a single day at home until the ordeal was done. When he did come home he was short one leg, lost to diabetes, and filled with contrition.

He was 51. By the following January he would be dead. I don’t think he knew it would be that soon, but he seemed to finally be reckoning with who he was, and what he’d done. He tried to connect with me, I think to begin to address how he’d harmed me.

I wasn’t having it. I gave him nothing. He was a bad person. My anger at him was righteous. And when he died, I felt relief.

I know that relief at the death of another person is not a good thing. But it was ok… I was a “Good Person”.

I was a Good Person. My dad was a Bad Person. So, it was fine that I felt no grief at his death. No need to examine that.

How did I know I was a Good Person? I wasn’t my dad. Who was a Bad Person.

So when I pressured my high school girlfriend into sex? Not a bad thing. Because I was a Good Person. And when I dumped her abruptly to pursue a new conquest? Still not a bad thing. That’s just how high school goes, and I am a Good Person.

When I borrowed $1,000 from the woman who let me live in her home because I was her boyfriend’s son’s friend, I never paid her back. But that was ok, other people never paid me back, and I was a Good Person.

When I participated in an affair with a married woman…

When I actively pursued a different married woman…

When I lied, took advantage of people, and chose things I knew would be harmful…

All of those were ok… because I was actually a Good Person.

I could not begin to reckon with the harms I’d caused until I removed the “Good” label from myself. I could not see others as whole, complex, and complicated people until I removed the labels I put on them.

I could not practice true empathy until I removed the lenses I viewed others and myself through. And without clear empathy, I could not fully make use of reason in my decisions. Where I thought I was starting from affected my destination.

It is difficult to live a moral life if we cannot witness other people for who they are.

It is difficult to live a moral life if we cannot witness ourselves for who we are.

No Halos, No Horns

All people, ourselves included, are not inherently good or bad. We are just people, driven by wants and fears, constructions of the materials we have inherited and choices we’ve made about how to put them together.

This does not mean we cannot assess a person’s actions as good or bad. We commit acts of evil when we choose to harm or choose to allow harm we could prevent.

But when assign a moral value to a person, it blunts our empathy for them. Then we judge anything through that existing moral view. And that view allows for harmful things to be excused when done by the “good”… it allows evil things to be done to those who are “bad”.

I excused a lot of harmful things I did with the logic of “well, I’m not my dad, who was Bad, which means I am Good, so if I did it, it must be ok.”

Here is the challenge: wipe the name off the file, examine the act, map the incentives and system around it, and enter it on The Ledger.

Is it a credit, a good that is affirming, that improves one’s material wellbeing, an act that increases someone’s dignity and freedom?

Is it a debit, a harm that causes damage, induces pain, destroys, corrodes, or dehumanizes?

Judge choices by their effects and their context, not by your feelings about the chooser, the doer of the deed.

That is how empathy avoids excuse and reason avoids cruelty.

“That thing they did was ok, because they are like me and I am a Good Person, therefore they did a good or neutral thing,” becomes, “Is what was done constructive and good, or destructive and bad?”

“This thing I am doing helps good people and harms bad people; therefore it is good,” becomes, “I am choosing to do harm to people. How can I instead choose to do more good for people absent a moral label on them?”

Empathy that doesn’t excuse harm. Reason that doesn’t empower evil.

We are all capable of either good or evil; the point is to become capable of recognizing both in ourselves first.

There are no good people. There are no bad people. There are good choices, good thoughts, and good acts. There are evil choices, evil thoughts, and evil acts. And there are people. Anyone can be better tomorrow, if they try, if they are allowed, and if they reckon with their yesterday.

If “Donald Trump is not a bad person” makes you flinch or cheer in agreement, then good, you’ve found a blind spot.

Swap the name, keep the act, and ask: what incentives and systems would make this outcome predictable for almost anyone? Then record it on the ledger: intent, consequence, agency, repair.

No halos, no horns.

Only choices and the responsibility and consequences they incur.

Empathy without excuse. Reason without cruelty.

Start there. Make clear choices. Be better tomorrow.

If you’re ready to explore practical philosophy for everyday ethical decisions, without the academic jargon, subscribe to Radical Kindness: Empathy as Rebellion. Every week, I share frameworks for navigating moral complexity, personal stories of growth through adversity, and tools for building a more ethical life.

Join a growing number of thoughtful readers who are figuring out how to be good humans in a complicated world.

Wow, such a great read! I really like how you explain this moral absolutism and I admire your ability to share the things in your life that you are not proud of. This feels like radical honesty and it’s really refreshing!