Can I Get a Witness?

The first step in keeping your moral ledger: learning to really see.

If you’ve read more than a handful of the essays in the archive you’ve come across some recurring concepts.

Witnessing. The Ledger. Reckoning.

This stuff has been bubbling in my head for years. Decades. So, when I talk about these concepts, they are the organization and identification of how I think every day. But I know I need to better explain and spell out what these mean in real life.

This will be the first in an ongoing series to dive into these concepts with greater nuance and show how they work when smashing into the complexities of everyday life. The ledger and reckoning will come later, right now we’re just staying with witnessing.

So, without further ado, I present…

Witnessing

· We owe each other witnessing. To see each other as people, to see how what we do, and what we don’t, affects one another." – What We Owe Each Other

· “Witnessing, true witnessing, leads to more than just charity. It colors how we think of and frame our place in the larger world.” – When Kindness Gets Pushback

· "See people. Witness them for what they are, not what you assign them to be." –Punk Philosophy

Obviously witnessing is fundamental to my conception of morality and ethics. But it’s not like people don’t see the bad shit in the world. The notifications are just waiting to pounce at us the second we look at our phone screens.

We all see the world on fire. What does it mean to witness within it?

First off, you’d be right to identify that there is a difference between seeing and witnessing. Witnessing is not just being aware of something. To witness you must see it, be aware, and engage. Witnessing is not passive, it is active.

Witnessing the harm matters. Where we direct our attention matters.

I’ll demonstrate. And don’t worry, the scenario I am about to share is not some example of my saintly behavior. Honestly, it is a record of me failing.

Failing a lot.

I was thirty-three when I finally got a job in finance, marking the beginning of my career. Until that moment I’d been squarely working in the blue-collar world; I’d spent time as a janitor, loading and unloading trucks, and behind the counter of a pawn shop.

Walking into the office on day one, two things were immediately apparent.

1) I was severely underdressed. It was day one orientation; I thought a polo and khakis were fine. When I saw everyone else in suits, I immediately realized they were not.

2) Sticking out in such a way only drove home something I already felt. I was an interloper in this world, and to stay within its walls I need to learn how to blend in.

That imposter syndrome colored much of my first few months on the job. For example, while I took to heart the company training and policies about not creating a hostile work environment and the concept of “bringing our whole selves into the office”, I knew that my success was dependent on navigating the unwritten rules, and the unofficial power structures.

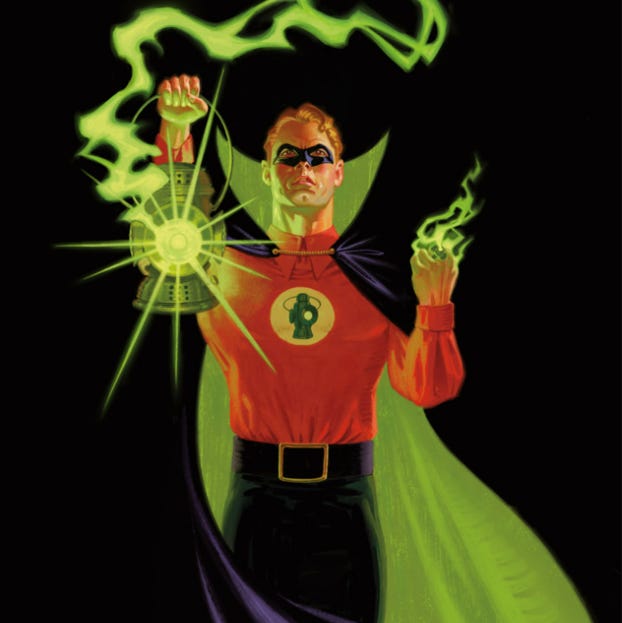

My first boss was a man who flouted every policy we’d learned in HR training. Knowing I was a nerd, he struck up a conversation about comic books. About how he was annoyed that DC Comics had recently revealed that Alan Scott, the 1940’s Green Lantern, was gay.

I knew about this already. It was rainbow capitalism and corporate tokenism in one go for DC. Alan Scott was not a beloved and well-known character. For most people the announcement elicited a shrug and a “who?”

But my new boss figured that the fact that I was a superhero geek and a regular (at the time) church attender meant I would be sympathetic to his rant about how DC made “The Green Lantern into a queer”.

And what did I do? Smile timidly, nervously chuckle at the inappropriate jokes. I disagreed with everything he was expressing. But I didn’t say anything. I just absorbed it and then went back to my desk.

On standby

Everyone knew this guy to be a boorish buffoon. Like he’d taken all of the memes about the conservative uncle you avoid at Thanksgiving and deliberately made it his personality. But he was very experienced in the industry and was a go to for upper management in dealing with complex risk scenarios. And his teams consistently performed.

Not to mention his ability to pave the way for the people who worked for him. He was good at identifying opportunities for advancement and matching people with them. To borrow a term from football, he had an extensive “coaching tree”, i.e. people in various leadership and roles of influence who gotten there in part thanks to him. He was connected.

I was no exception either. He got me put on to a specialist team before I had really earned the opportunity. But he saw the potential. And he was right. It set my career track on a higher trajectory from the jump. And not only that, as I climbed the ladder I did so with him putting his thumb on the scale in my favor.

So when we became peers, I still didn’t feel like his equal. And just like everyone else who saw his terrible behavior, I laughed it off as “him being him”, our crotchety office grouch.

But I knew better. I knew how his casual homophobia kept other people in the closet. I saw his tossed off antisemitism keep a Jewish employee’s head down.

And when we became peers? I watched every day as he made lewd comments about our boss. Not out of his attraction, which wouldn’t excuse it, but to undermine a woman in power.

I saw it all. For years. What did I do? Tell my employees to ignore it. Tell them he brought a lot of unique experience to the org, that he knew “where the bodies are buried”. I’d seen him shut down HR complaints about someone on his team before. I could only imagine what would happen if he became the focus of an investigation.

Best case scenario? He is reprimanded or even fired, but in the process makes himself a martyr being punished by “wokeness”. And that would not be a quiet process.

Worst case? Nothing changes for him, but I am identified and my influence essentially quarantined. “His people” would freeze me out, and he’d make me an example of why you shouldn’t take this to HR by eroding my influence and making me out to be a disloyal villain.

“I made that guy’s career, and this is what he does to me?”

You can’t be this much of an asshole if you can’t supplement it with charm and charisma. Otherwise, he’d never have gotten to the place where he could do so much damage.

And if he walled me off, I’d not be able to do the things I recognized I needed to do.

My father was deeply abusive. But when someone finally reported him, he easily talked his way out. I could see that with this guy at work. Being a white guy who is “normal” lets you start with the benefit of the doubt few others get. So, I didn’t rock the boat, for fear of damaging my own career.

I grew up poor. I never wanted to go back.

I was seeing this guy. I was seeing his harms. I was witnessing them. Because with every comment he made I didn’t push back against, I was logging an evil of indifference. Every 24-year-old fresh from college, I was giving them permission to mirror that behavior.

And every woman or person of color? I was communicating to them that they didn’t truly belong. The exact feeling I was dealing with.

No, not the same. I’m a heteronormative appearing white man. I can blend. For women and POC’s? this guy could always make them feel like the “other”. Just the way he liked it.

For five years I accumulated debits as a passive enabler.

For five years I saw the impact on people. People who felt the need to hide themselves in the office. People who felt the need to reach for a higher standard to just be accepted, even though this guy never would accept them as equals or peers.

I was seeing. But I needed to witness.

When I was promoted to be his peer, I now sat right next to him. He greeted me every day by undermining our boss with a sexually demeaning comment. All of our employees could hear it.

After a few weeks of this, facing it up close, I finally decided I could tolerate it no more.

Step one was finally acknowledging my culpability in the situation. Sure, I wasn’t making racist and misogynistic comments. But I was allowing an environment where they could be said without challenge. I knew why the black guys on his team would be his go to for handling difficult situations but not get a vote from him for a promotion. I knew why he referred to his former assistant manager as his secretary long after she’d become the clearly best manager in our org.

I was even in a group chat with him and other managers, where screenshots of any conversation would have been enough to take to HR. But still, nothing from me.

And now that I was his peer, my capacity, and my obligation, were increased. I knew it. So what did I do?

I did not file an HR complaint. That would have been the policy defined process for addressing it. But I also understood the consequences. If he knew it was me, he’d run an effective campaign to ostracize me and whittle away my influence. Higher level leadership who valued his contributions would explain away or pay lip service to anything brought to light.

I want to be clear though, my lack of action was not driven by a desire to not “ruin his career”. He’d negatively impacted the careers of as many people as he’d helped, in the grand scheme of things I felt no obligation to protect him from his malice. And the solution that I arrived at was by no means perfectly effective. Even pushing back, I was still recording debits in my ledger.

But I need to add credits. I recognized the reputation I’d developed over the years. A neurotic but fair manager who tried to set up my employees to succeed and advance. Not only that, but a genuinely decent and moral person.

I started by no longer allowing the things this guy said to pass without challenge. Calling out his “jokes” as harmful. Pointing out his flawed logic about people he was prejudiced against. Reframing his comments in ways that highlighted their absurdity, undermining his influence with our impressionable young employees and trying to plant seeds of logic in his mind.

I stopped telling people his behavior could be excused because of his expertise. I began using him as an example of not to succeed, pointing out his failure to advance despite many attempts and interviews.

I didn’t stop his behavior. When I left that org he was still as buffoonish as when I came in. But I’d changed the way he was perceived. I actively addressed the harmful behaviors he did and made it uncomfortable for him to continue doing them. I elevated the people he pushed down by joining groups like our women’s leadership affinity group as a mentor and visibly supporting both our black professional group and LGBTQ inclusion group.

I was aware of his reputation and my own, as well as our respective levels of influence, and I cultivated mine to counter his. All the while we literally sat side by side.

I’ve since moved on. He’s still there. But I know in my years of leadership as his peer, I helped to promote a cadre of people in positions of influence, like he had. But mine disproved his narrative that only white men truly belong.

I still failed.

A lot.

But every day I recognized the impact of his behavior, and my influence in either tacitly approving it or pushing back against it.

I witnessed my failures. I witnessed my successes. I learned. I took responsibility for what I saw.

And I promised to be better tomorrow.

Witnessing is the first step. We have to see the good and bad in the world, understand our place in relation to it, and engage.

And like even the best baseball players, we will fail a lot more than we succeed. After all, a .333 batting average will make you an all-star, but it still means you failed to get a hit in two out of three at bats.

But you still take your swings. Fail, see it, learn and improve.

Can I get a witness?

We all face little harms in the world directly around us. And we can see how to introduce more good into the world too. To do it, we need to do more than see.

We need to witness.

When have you born witness to something without an easy fix? Share the harms you have witnessed, and the good you created in response.