Anything Tomorrow?

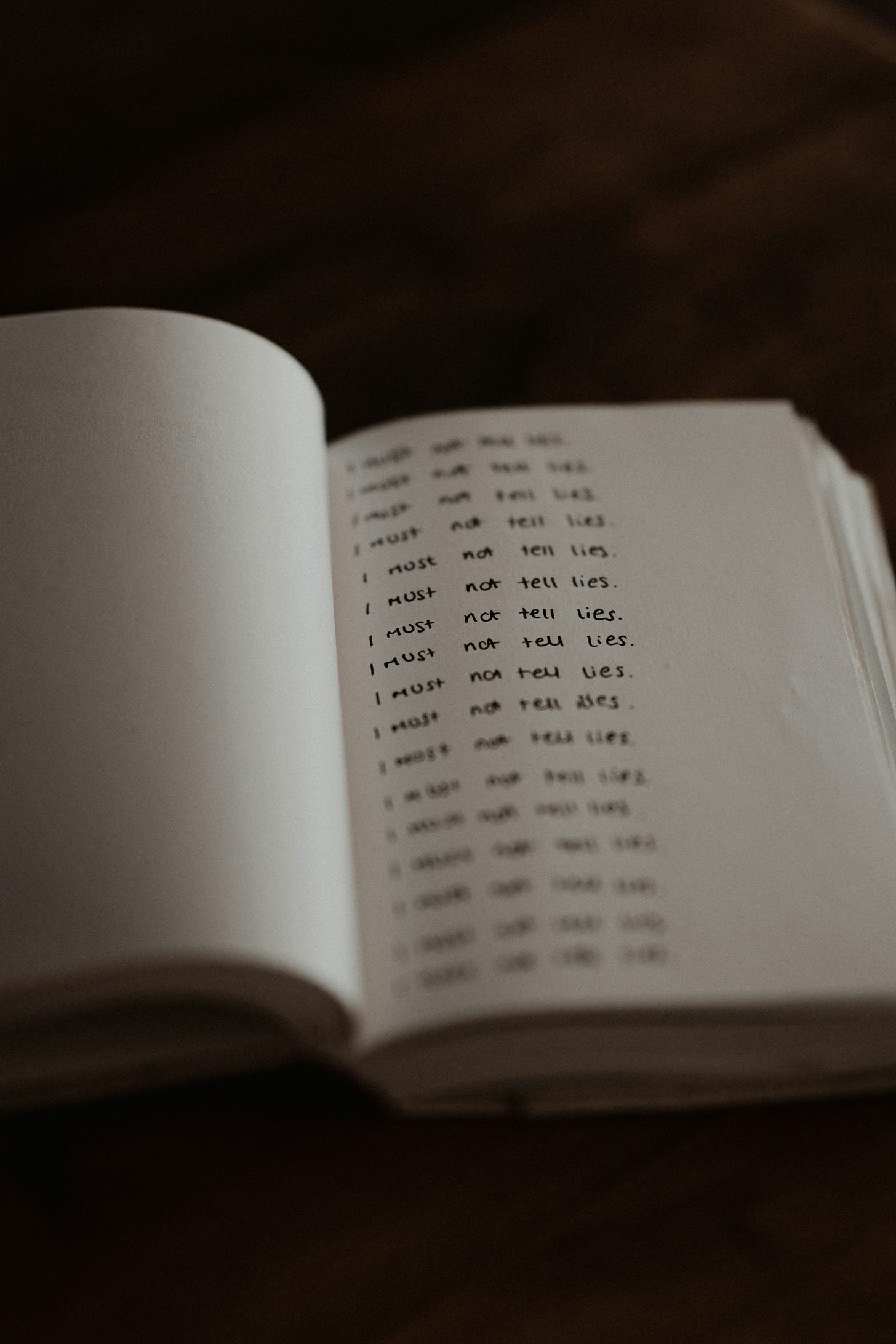

How do you reconcile a truth that hurts with a lie that doesn't?

I have learned a lot about dementia in the last four years. Particularly the importance of routine.

My wife and I bought a larger house in March 2021 to give us the room for her mother to live with us. When she first moved in, she still had some measure of independence. She couldn’t remember the month or day of the week, but she could pick out her clothes and do small chores around the house.

Routines helped. In the morning, she woke up, showered and dressed, made herself a cup of tea and a bowl of cereal, and took her morning medication. At bedtime she took her evening medication, changed into PJ’s, and inquired about what was happening the next day.

“Anything tomorrow?” she’d ask.

One of us would let her know if she had a doctor’s appointment, or if we had plans like a movie or activity for her.

Slowly, those routines began to erode.

Now one of us makes sure she is up in the morning. We give her clean clothes and make sure she doesn’t have the dirty ones from the day before. Once she has dressed, we check to make sure everything is on correctly. One of us makes her tea and breakfast.

At night we give her the evening meds and make sure she actually changes into PJ’s. Before she goes to bed, she still asks, “Anything tomorrow?”

The answer is mostly irrelevant. If there is something tomorrow, she won’t do anything to prep for it. She doesn’t need to; we’ll have it all taken care of. By the time she goes to sleep it will be gone from her mind.

There is a complicating factor. Unlike most people who suffer from Alzheimer’s, she is aware of her condition. And that awareness makes her very anxious about any situation outside of her comfortable routine.

When she asks, “Anything tomorrow?” telling her that there is something induces only stress. No matter what the actual answer is, I have taken to always to answering, “No.”

When she has an appointment, or her watercolor class, or a day scheduled at a senior center, my “No” is a lie.

The question for me is this. Is telling her “No” in these scenarios wrong?

Immanuel Kant would say that lying to my mother-in-law is wrong. Because lying is always wrong. According to Kant, the consequences of an action do not determine their morality. A lie is a lie. If a, lie is ever wrong, it is always wrong.

Honestly, I agree. My lies to my mother-in-law are wrong. I know that. And I still tell those lies.

As a person, it is not possible to never do wrong. The world doesn’t work that way. It is this basic fact that forms a pillar of Ledger Ethics.

When I lie to my mother-in-law, I recognize that I have chosen to do something wrong. I have chosen to not treat her with her full human dignity and respect. Because that is what we all do when we lie to someone. It is an evil I have committed.

I have my reasons. Telling her we are going to the doctor tomorrow will cause her stress and generate nothing good for her. Allowing her to remain unaware may slightly benefit her by allowing her to avoid the anxiety, but any good does not wipe out the bad.

Recording a good in my moral ledger does not erase the evil I did. They are both there forever.

But it’s more than just the occasional lie. Every choice we make changes us, in ways that may not be obvious, but each is a part of the ongoing construction of who we are.

By giving myself permission to do a small evil, how does that change me? It may mean that in a future situation where the choice is murkier, I may choose a lie over the truth. After all, the neural paths in my brain that allow for a lie have been made a little stronger.

Changes often aren’t made at once. When my mother-in-law moved in with us, she still had a lot of capability despite her condition. Four years later, she has lost most of that capability. It wasn’t a sudden change. It was the culmination of many small changes.

The little lies I tell her matter to the person I am constructing. What happens if I don’t face them for what they are? If I explain them away as justified because the truth will only hurt and not help?

I will probably continue to lie about plans tomorrow. I love my mother-in-law and I don’t want any hurt to come to her. Seeing her anxious about the smallest things breaks my heart.

But I also must be honest about what telling those lies does to me. I can be better tomorrow. But that only happens when I am honest about the wrong that I do.

If you’re ready to explore practical philosophy for everyday ethical decisions, without the academic jargon, subscribe to Radical Kindness: Empathy as Rebellion. Every week, I share frameworks for navigating moral complexity, personal stories of growth through adversity, and tools for building a more ethical life.

Join a growing number of thoughtful readers who are figuring out how to be good humans in a complicated world.

God, Anthony, this is beautifully written! It made me tear up a bit. I hope your mother in law will have many a peaceful evenings, with nothing tomorrow